When governments and health agencies talk about “mortality improvements,” two statistics often get pride of place: the Age-Standardised Mortality Rate (ASMR) and Life Expectancy at Birth.

Both sound objective. Both have long pedigrees in official statistics.

And both can paint a deceptively optimistic picture when raw deaths are rising.

What These Measures Actually Are

Age-Standardised Mortality Rate (ASMR) isn’t a count of deaths.

It’s a modelled rate that answers a hypothetical question:

“If everyone in our population had the same age structure as a fixed ‘standard’ population, what would the overall death rate be?”

The intent is to remove the influence of ageing. If one country or year has more elderly people than another, the crude death rate will naturally be higher, even if people aren’t actually dying sooner.

ASMR levels the playing field by applying each age group’s death risk to a constant population template—often the WHO World Standard or the NZ 2001 Census Standard.

Life Expectancy at Birth works in a similar way. It isn’t a forecast of how long babies born this year will live. It’s a model that assumes today’s age-specific death rates will remain constant forever.

It’s an age-weighted summary of current risk, not a measurement of actual lives lived.

Why They Can Move in Opposite Directions to Reality

When New Zealand’s total deaths rise but the ASMR falls, both numbers are technically correct.

They’re simply answering different questions.

ASMR reflects risk per age group.

Crude or excess deaths reflect how many people actually died.

An ageing population means there are far more people in high-risk age brackets. Even if the risk of death at each age keeps falling, the sheer number of older people can lift total deaths and excess mortality.

The same effect applies to life expectancy: a large rise in deaths among the elderly can coincide with an increase in life expectancy, because those deaths occur at ages that carry little statistical weight in the calculation.

The “Smoothing” Effect

Both measures deliberately smooth away demographic change.

They hold the population structure constant, so population ageing is ignored.

They apply fixed weights that may under-represent groups where mortality is actually surging (for example, the very old or newborns).

They give the appearance of stability even during sharp real-world shifts.

That makes ASMR and life expectancy useful for long-term epidemiological modelling, but risky as public indicators of current outcomes.

They can make a record number of deaths look like “improvement”.

A Simple Example

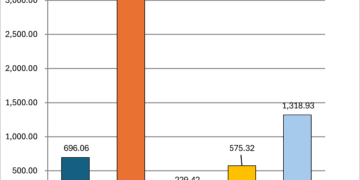

Imagine a population where the 85+ group doubles in size, but its death rate falls slightly:

| Year | 85+ Population | 85+ Deaths | Rate | Total Deaths | ASMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 80 000 | 8 000 | 10 % | 30 000 | 600 /100 000 |

| 2025 | 150 000 | 10 000 | 6.7 % | 35 000 | 500 /100 000 |

Deaths increased by 5 000, but the age-standardised rate fell.

The model sees lower risk; the public sees more funerals.

Both are right within their own logic.

When It Matters

If you want to know how many people died who wouldn’t have, you need raw or per-capita data and a clear baseline.

That’s what excess-mortality analysis captures.

If you want to know whether each age group’s risk of death has changed, ASMR is the right tool.

But if an agency uses ASMR or life expectancy to claim that “mortality is improving” during a period of record deaths, that’s a change of subject, not a discovery.

A Better Practice

For clarity, any mortality report should show three parallel views:

Crude deaths and per-capita death rates — the literal experience.

Excess mortality — deviation from recent baseline.

Age-standardised rates — underlying risk independent of age structure.

Together they reveal what’s driving the change: ageing, risk, or both.

Separately, any one of them can mislead.

The Bottom Line

ASMR and life expectancy aren’t fraudulent, but they are context-dependent.

They describe risk, not reality.

In a rapidly ageing country like New Zealand, that difference matters more each year.

When “improving” statistics coincide with full mortuaries, it’s worth remembering:

what’s being standardised away is often the very thing people are living—and dying—through.