Why ASMR Isn’t the Final Word on Excess Mortality

During discussions around New Zealand’s COVID-19 mortality outcomes, one metric repeatedly appears: Age-Standardised Mortality Rate, or ASMR. Some commentators argue that because ASMR in 2021 and 2022 was comparable to or even below prior years, there was no excess mortality worth worrying about. This, they claim, proves that the COVID-19 response was safe and effective.

But that claim doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. Here’s why.

What ASMR Does Well

ASMR is designed to allow comparisons across populations and time by adjusting for age structure. In a country like New Zealand, where the population is gradually aging, crude death rates can rise simply because more people are reaching older, higher-risk age brackets. ASMR helps control for that.

It is excellent for long-term analysis of diseases with relatively stable age-specific death rates, like cancer or cardiovascular disease. It’s a valuable public health tool.

What ASMR Fails to Capture in the COVID-19 Context

1. Novel Events Are Not Predictable by Long-Term Averages

ASMR relies on historic age-specific death rates. For a novel virus with unknown dynamics and a completely new medication rollout (mRNA-based vaccines), these baselines are no longer valid predictors. When the risk landscape changes dramatically, age-standardisation based on pre-pandemic norms becomes disconnected from reality.

2. ASMR Obscures Absolute Numbers

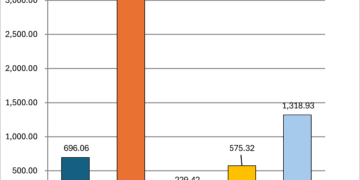

In 2022 and 2023, New Zealand recorded significantly more raw deaths than in pre-pandemic years. ASMR may remain stable due to changing population structure, but that doesn’t mean the public health burden was unchanged. It just means the rate, as calculated per 100,000 age-adjusted people, didn’t increase significantly. If 3,000 extra people died, that’s still 3,000 more funerals, regardless of whether the population was slightly older.

3. It Misses Timing of Spikes

Excess mortality often presents in waves. ASMR, particularly annualised, smooths these spikes. For example, sharp mortality peaks in July 2022 and December 2023 are diluted across a 12-month average.

4. ASMR Doesn’t Separate Causes

ASMR can’t tell us why people are dying. It doesn’t distinguish between COVID-19 deaths, vaccine-related adverse events, deferred care impacts, or seasonal illness. It only tells us that, age-for-age, death rates are similar. But if the causes shift drastically, that similarity is misleading.

5. Rolling Averages or Baseline Comparisons Show a Different Story

Using a five-year rolling average baseline (2015–2019), New Zealand has consistently recorded excess deaths since late 2021. This method simply compares observed weekly deaths to expected weekly deaths based on prior years, adjusted for seasonality but not standardised by age.

Unlike ASMR, this approach doesn’t obscure spikes, nor does it pretend that a shift in the age structure nullifies the impact of unexpected mortality.

The ASMR Fallacy: Safety by Standardisation

Some public health advocates are using ASMR to argue that New Zealand’s pandemic response was a clear success with no mortality downside. But this is a misapplication of the metric. It’s the same logical sleight-of-hand used to claim that 80,000 deaths were avoided, based on theoretical models that never materialised.

It is entirely possible for ASMR to be flat or negative while thousands more people die than in prior years. That’s not a contradiction. It’s a feature of how ASMR is constructed.

ASMR, like Hendy’s 80,000 death scenario, can be framed to sound definitive, when in reality it’s highly dependent on assumptions, context, and intent.

In both cases:

The models or metrics were treated as absolutes by media and officials.

Most people never saw the assumptions, limitations, or alternatives.

When reality didn’t match the worst-case scenario, it was declared a success, rather than questioned whether the model had been valid in the first place.

ASMR, like that model, works best when applied to stable, well-understood causes of death (like cancer or heart disease), where historical age-specific death rates are consistent. But it loses reliability in novel, chaotic events like pandemics with new variables: border controls, a brand new vaccine, behavior changes, and changes to death certification criteria.

The people telling you “ASMR proves we had no excess deaths” are making the same mistake as those who claimed “the vaccine saved 30,000 lives”: they’re treating one interpretation as unchallengeable truth.

Conclusion

ASMR is a useful metric in stable conditions. But in the context of a novel pandemic, changing medical interventions, and fluctuating population dynamics, it is not a reliable way to measure excess mortality.

If the question is, “Did more New Zealanders die than we expected based on historical norms?” — then ASMR is the wrong tool. Look instead at raw deaths, week-by-week comparisons, and age-group specific mortality in context.

In short: ASMR can obscure more than it reveals when deployed in a crisis.

This article is part of the ongoing “What the Data Shows” series, examining statistical claims around COVID-19 in New Zealand using government datasets and strict mechanical fidelity.