In 2022, New Zealand’s COVID-19 response entered a new phase. The urgency of the first two-dose rollout had given way to the subtler, more complex territory of boosters, eligibility shifts, and the emergence of Omicron. With the virus evolving and the public’s patience fraying, the Ministry of Health and government officials were faced with a new challenge: maintaining trust while adapting the message.

This article explores how vaccine-related messaging and reporting evolved throughout 2022 — and how the shift from certainty to complexity shaped public perception.

The Booster Era Begins

As Omicron loomed at the start of 2022, public health authorities ramped up messaging around booster shots. Though New Zealand had some of the highest two-dose coverage rates in the world, health officials quickly recalibrated expectations, warning that protection could wane without a third dose.

The language used was both urgent and familiar. Boosters were framed not as optional upgrades, but as essential to full protection — “your best defence,” “your next step,” and “part of staying up to date.” This marked a rhetorical shift: what had been a complete vaccination course in 2021 was now only the beginning.

Evolving Definitions of “Fully Vaccinated”

Another element that added to the confusion was the shifting criteria around when someone was considered “fully vaccinated.” Initially, in line with international guidance, the Ministry of Health defined full vaccination as two weeks after the second dose. This period was meant to reflect the time required for the immune system to respond effectively to the vaccine.

However, as the booster rollout progressed and Omicron began spreading rapidly, this window was adjusted. At different points, the criteria narrowed to just seven days after the second dose — a change not always clearly communicated to the public. These shifts, while grounded in evolving scientific understanding, contributed to a growing sense of opacity. People who had received their doses in good faith now had to recalibrate their status based on changing thresholds.

In a Ministry press release from February 2022, Director-General of Health Dr. Ashley Bloomfield noted, “We now consider someone fully vaccinated seven days after their second dose rather than the previous 14 days, based on updated evidence about immune response timing” (source).

This evolving benchmark raised additional challenges for public understanding. For example, it affected who was counted as “fully vaccinated” in hospitalisation and death statistics — which, in turn, impacted perceptions of vaccine effectiveness. Critics argued that this moving target could have the unintended consequence of undermining confidence among those already hesitant.

One of the most notable shifts in 2022 was the subtle redefinition of what it meant to be “fully vaccinated.” While early Ministry dashboards and press briefings had proudly proclaimed high two-dose coverage, by mid-year, the focus had pivoted to booster uptake.

However, the language often avoided direct confrontation with this change. Rather than announcing a formal reclassification, the Ministry used phrases like “additional protection” and “recommended boosters.” For many, the implication was clear — but the message was designed to avoid alienating those who had already completed the original course.

This careful balancing act — between medical accuracy and political palatability — was a hallmark of 2022’s communication strategy.

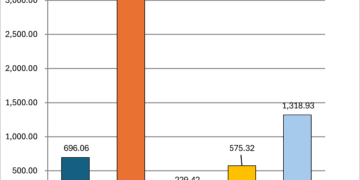

The Numbers Shift

In March 2022, the Ministry reported that 94% of eligible people aged 12+ had received two doses. But what counted as “eligible” still depended on the Health Service User (HSU) dataset — a model based on interactions with the health system. When compared with New Zealand’s total estimated population, the actual two-dose coverage was closer to 77%.

This disparity, while not new, became more significant as public scrutiny of booster statistics grew. With HSU denominators unchanged, booster uptake appeared high — but many suspected that the real coverage was lower. Trust in the numbers, once near-universal, began to show signs of strain.

Language of Social Cohesion

Archived snapshots from the Wayback Machine in 2022 reveal a consistent use of behavioural science principles to nudge vaccine uptake. Key strategies included:

- Framing Boosters as Essential: Public health messaging consistently portrayed boosters as necessary rather than optional, using terminology like “stay up to date” to reframe continued vaccination as a standard expectation.

- Appeals to Community Responsibility: Messages emphasised protecting the vulnerable, such as the elderly, immunocompromised, or kaumātua. Some campaigns and Ministry statements invoked Māori values of whanaungatanga (kinship) and the importance of protecting one’s whānau, especially kaumātua, as part of the broader vaccination appeal. This reinforced social norms and invoked moral obligation across diverse cultural groups.

However, this messaging often implied that by getting vaccinated, individuals could help protect others around them. While vaccines were primarily designed to reduce the severity of disease for the person vaccinated, early public communications sometimes gave the impression that they significantly reduced transmission as well. Protection against transmission was never an absolute. - This framing, whether intentional or not, supported the broader public health aim of encouraging collective action. But it also blurred the line between self-protection and community benefit. The assertion that one’s vaccination protected others may have had a strong nudging effect — particularly when framed in the context of protecting elders, whānau, or the broader community.

- Simplified and Repetitive Messaging: The frequent use of direct, easy-to-remember phrases helped reinforce the core messages and made them accessible to a wide audience.

- Use of Trusted Voices: Authorities consistently leaned on familiar figures — like Dr. Ashley Bloomfield and Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern — to deliver key messages, leveraging public trust.

- Highlighting Consequences of Inaction: Messaging sometimes underscored potential outcomes of non-vaccination, such as severe illness or exclusion from social activities, to increase the salience of risk.

These techniques align with established behavioural science strategies that aim to shift public behaviour subtly through framing, without coercion. In New Zealand’s case, this helped maintain one of the highest vaccination uptakes globally, while also raising questions about the balance between persuasion and transparency.

Despite the growing complexity, the Ministry maintained a tone of social unity. Much like in 2021, phrases like “do it for your community,” “protect our most vulnerable,” and “let’s keep each other safe” continued to dominate public messaging. But by mid-2022, such language was increasingly paired with reminders of waning immunity and calls to remain “up to date.”

This blend of social responsibility and personal maintenance signalled a change in public health framing — from a one-time act of solidarity to an ongoing, individual obligation.

Despite the growing complexity, the Ministry maintained a tone of social unity. Much like in 2021, phrases like “do it for your community,” “protect our most vulnerable,” and “let’s keep each other safe” continued to dominate public messaging. But by mid-2022, such language was increasingly paired with reminders of waning immunity and calls to remain “up to date.”

This blend of social responsibility and personal maintenance signalled a change in public health framing — from a one-time act of solidarity to an ongoing, individual obligation.

Cautious Confidence and New Metrics

By the end of 2022, authorities were speaking with cautious confidence. Deaths were decoupled from case numbers, hospitalisations remained manageable, and regular booster updates continued.

Yet the numbers were harder to interpret. With changing definitions of vaccination status, the rollout of second boosters for specific groups, and seasonal waves of infection, the public faced an increasingly layered data landscape.

Charts once used to celebrate milestones now required footnotes. “94% of eligible” still appeared — but fewer were certain what that meant.

COVID Deaths and Cause Clarity

By mid-2022, New Zealanders began hearing more frequent reports of “COVID deaths” in daily updates. But beneath the headline figure was a key detail: many of these deaths were based on a reporting standard of death “within 28 days of a positive test,” rather than confirmation by a coroner that COVID-19 was the primary cause.

The Ministry of Health clarified that not all reported COVID-related deaths were the direct result of the virus. In some cases, individuals had underlying conditions or died from unrelated causes but had tested positive for COVID-19 recently. For most of these deaths, no formal coroner’s determination was required. This reporting method followed an international convention for rapid surveillance — but also introduced ambiguity.

One widely publicised case was that of a young unvaccinated man who was fatally shot in his driveway in New Lynn, Auckland, on 5 November 2021. The man had recently tested positive for COVID-19, and his death was initially included in the official COVID-19 death figure, showing that 33% of Covid deaths that week were unvaccinated.. This was despite the cause of death being a gunshot wound — a case clearly unrelated to COVID itself. During that week, the only other known COVID deaths were two fully vaccinated elderly individuals. While the Ministry later clarified the nature of his death, the inclusion in official statistics raised concerns about how the public might interpret these figures.

Archived statistics from the Ministry of Health’s COVID-19 Case Demographics page for that week can be viewed here.

Public health experts defended the approach as necessary for real-time monitoring, while critics argued that it blurred the line between dying “with” COVID and dying “from” it. The distinction became especially important for public trust as the booster rollout continued.

If the public perceived all COVID-positive deaths as being caused by the virus — even when not medically confirmed — it could have influenced behaviour. From a behavioural science perspective, this framing may have had a nudging effect: amplifying perceived risk to encourage vaccine uptake, particularly among those who were hesitant or undecided about boosters.

While not deceptive in intent, the practice raised important questions about how mortality is communicated during a public health campaign — and whether the framing of risk, even when technically accurate, can shape public sentiment in ways that warrant further scrutiny.

Looking Ahead

In 2021, the challenge was convincing people to get vaccinated. In 2022, the challenge was maintaining clarity and confidence as the situation evolved. But by the end of the year, it was clear the government’s aim had shifted once again — not just to inform or reassure, but to sustain momentum. With booster fatigue setting in, and vaccine hesitancy persisting among some groups, the language of public health messaging became increasingly focused on continuity.

Messaging continued to emphasise the need to stay “up to date” with vaccinations throughout 2023. Public updates, campaigns, and signage all reflected a new goal: to normalise ongoing vaccination as a routine civic responsibility, similar to a seasonal flu jab — but underpinned by the same appeals to solidarity, risk reduction, and community protection seen in earlier phases.

The story continues into 2023, where the campaign’s next chapter would need to contend not only with evolving science — but with evolving trust.